INPUTS, OUTPUTS & OUTCOMES

As you review this, keep in mind that this is not advocating that organizations measure everything. Not everything you care about needs to be or should be formally measured. Not everything can be measured. And everything you measure incurs a cost. Your organization should ‘Goldilocks’ what it measures. You should only capture measures that help your organization make better decisions to increase impact (and are practical to collect).

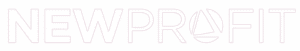

Inputs

Inputs are measures of the investment of people, time and money in your campaign.

On this website, we focus largely on outputs and outcomes (and infrastructure). However, it is important for organizations to articulate inputs in order to assess how well their allocation of scarce resources (investment) achieve their intended outcomes (return).

Outputs

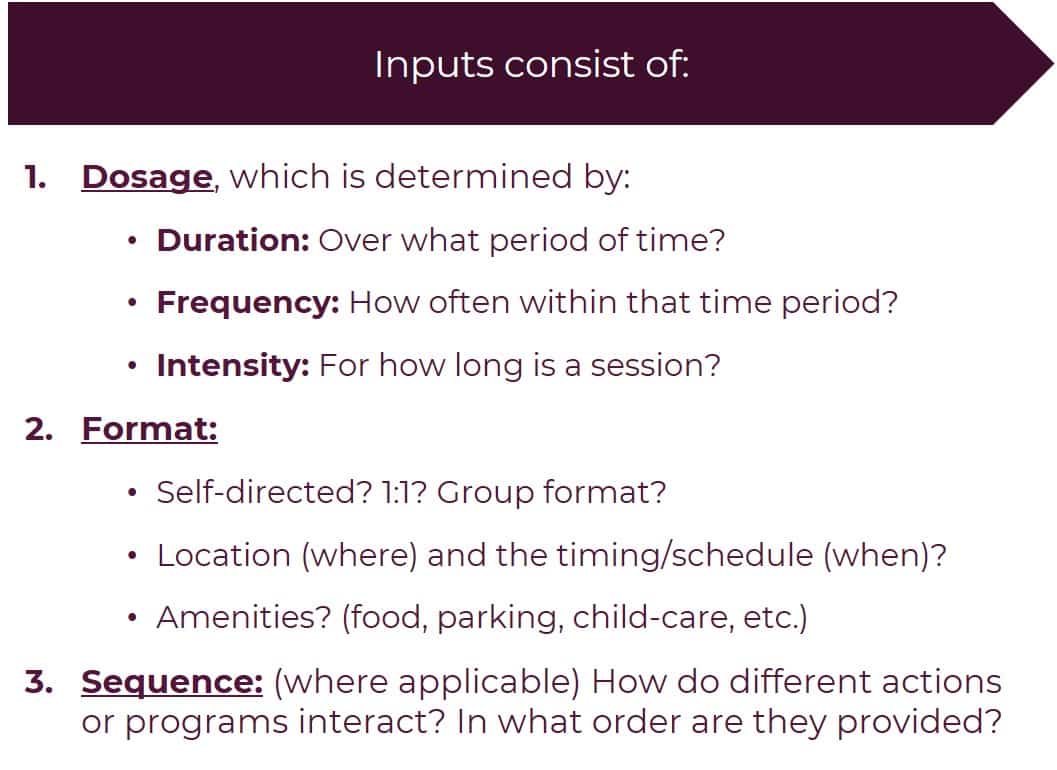

Outputs are the measures of reach or engagement/participation in your campaign.

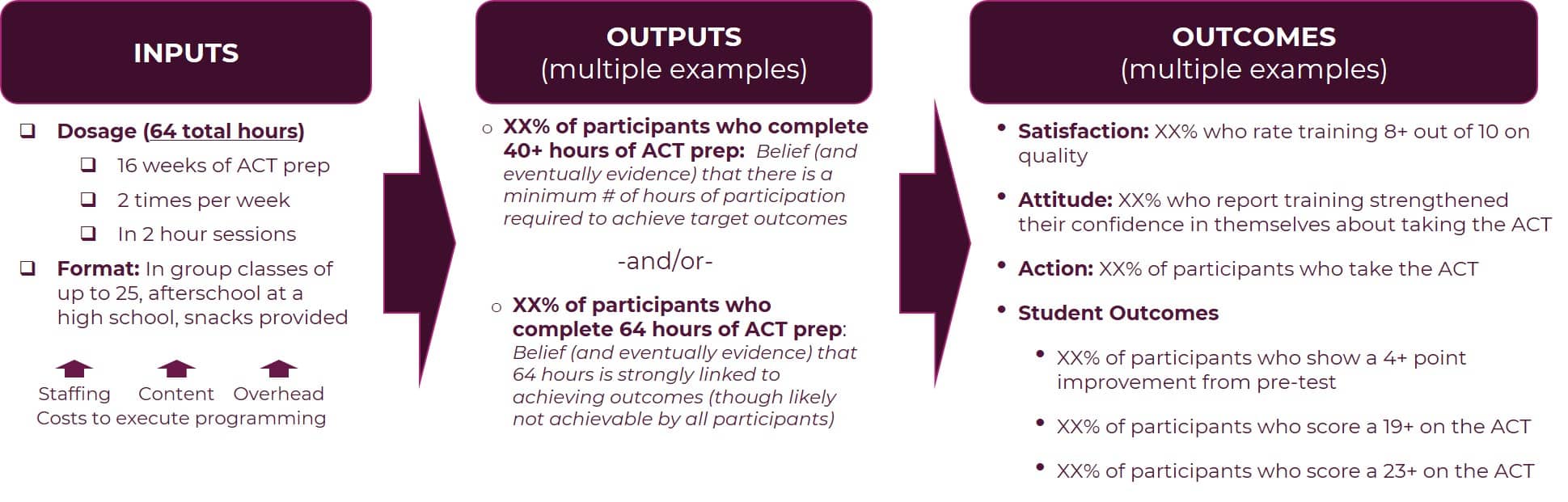

Some outputs involve the completion of a certain number of hours of participation in programming, which underscores the importance of laying out the dosage in the inputs, as this then determines how to quantify outputs (see the ACT prep example below).

Outputs are not the same as outcomes, but they are important to measure because they tell you if you are more or less likely to achieve your desired outcome(s).

However, outputs are also not a substitute for outcomes.

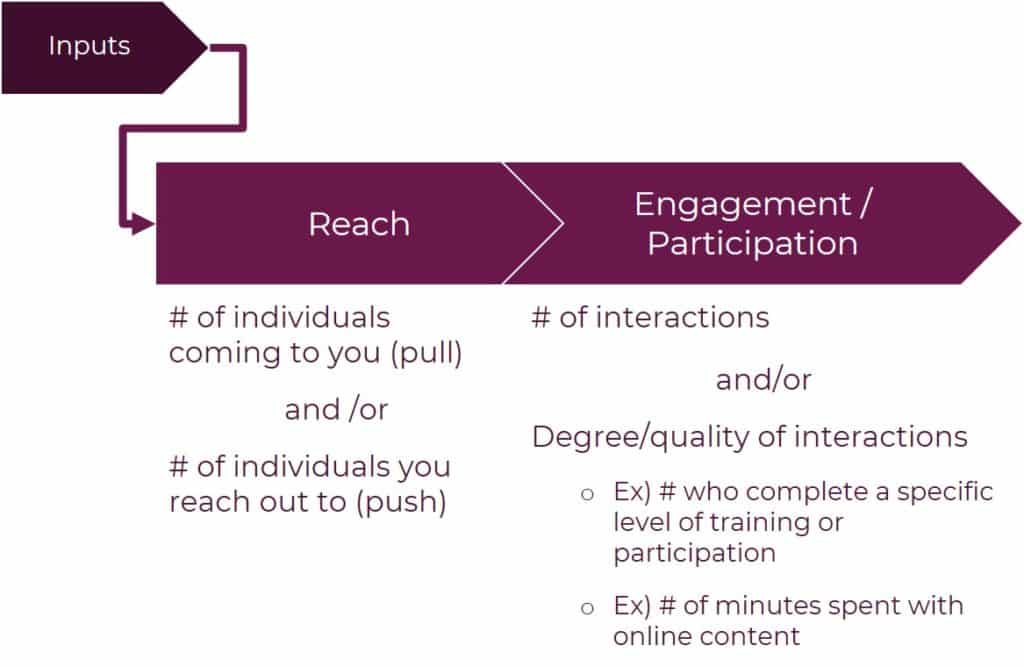

Outcomes

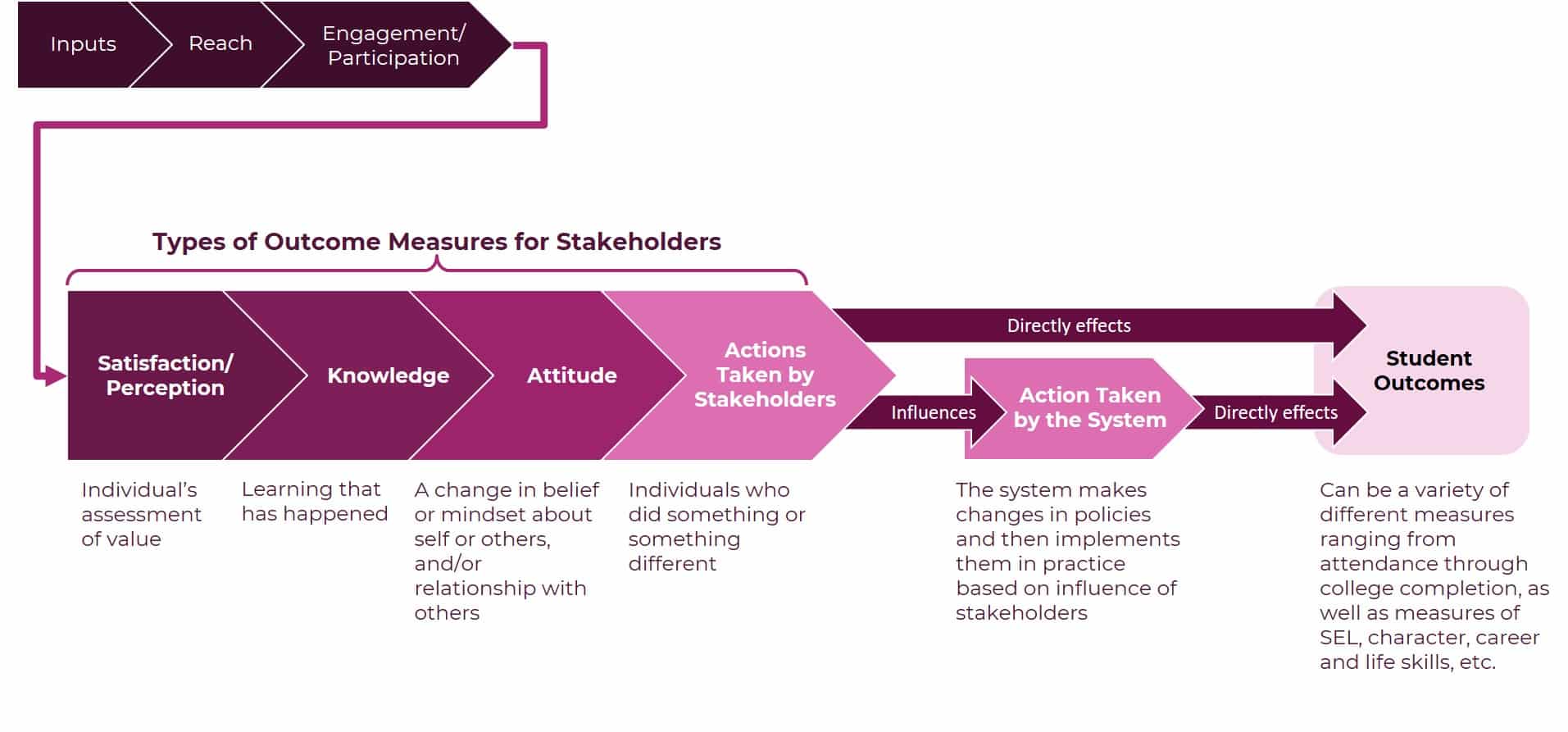

Outcomes are the measures of benefit or change that your campaign creates.

There are many different types of outcomes an organization can measure to understand if it is creating benefit or change. In education, improving student outcomes (in all the complex and rich varieties these can be measured) is an organization’s ultimate goal. However, an organization can measure a range of preceding outcomes to help understand whether a campaign is on or off track to positively impact student outcomes.

“Measuring satisfaction enables us to know if we and all of our stakeholders perceive the same existing reality.”

— Samantha Cohen

Senior Managing Director, Family and Community Engagement

Flamboyan Foundation

Satisfaction/perception is often the most immediate outcome to measure from programming. High satisfaction is not an automatic assurance that the ultimate desired set of other outcomes you want will happen. However, low satisfaction with an organization’s programming can serve as an immediate warning sign that other types of outcomes are less likely to happen. “Measuring satisfaction enables us to know if we and all of our stakeholders perceive the same existing reality. It also lets us know very quickly if our programming is or is not working to meet the needs of our families,” advises Samantha Cohen, Senior Managing Director of Family and Community Engagement at the DC- and Puerto Rico-based Flamboyan Foundation. Some organizations do this through surveys. Some surveys include a concept called a Net Promoter Score which measures the degree to which participants would recommend your organization or programming to their peers.

Knowledge lets an organization know if learning is happening that it believes is a necessary precursor to changes in action. This outcome could include knowledge about the performance of a parent’s child, their child’s school or their community’s school system. It could include knowledge about the policies and politics that drive that performance, including who has authority. A knowledge measure could also capture how a parent could do something different – individually for their child or collectively as a group. Organizations can measure knowledge through self-assessment via a survey or a pre- and post-test.

"Measuring how far down a web page a parent reads, or for how long they watch a video, tells us which information and messages they are and aren’t getting exposed to. It informs how we craft our future content so we can succeed in providing the knowledge parents value most."

— Donovan Birch Jr.

Digital Strategist

Innovate Public Schools

In the internet era, organizations can also assess knowledge by observing where people spend time with an organization’s online content. For example, did the person watch a video or download a report? How far into a video did they watch on average? How far down an article or page did they scroll on average? These can tell an organization a lot about which knowledge in a video, article or page is being consumed or not consumed by their intended audience. “Measuring how far down a web page a parent reads, or for how long they watch a video, tells us what information and messages they are and aren't getting exposed to. It informs how we craft our future content so we can succeed in providing the knowledge parents value most,” counsels Donovan Birch Jr., Digital Strategist at Innovate Public Schools.

In Parent Empowerment work, Attitude is a measure that helps organizations assess whether individuals have made a shift in their belief about the innate power they hold, the potential for their child’s achievement, and/or their beliefs about what an educator or education system can and should be able to do for their child. Changing attitudes do not automatically mean a change in actions, but it can be a good predictor. However, asking a parent to reflect on their attitude can be catalytic because it is asking them to judge if they believe they have the power to make change happen for their child. When the answer is “yes”, it is both self-affirming and self-inspiring.

Actions involve someone doing something or something different with the intent that it leads to educational impact. In campaigns to support parents exercising their power as partners in education or by exercising their choice, parents take direct action that – if succeeding in its intent – directly impacts student outcomes. However, in collective voice (issue) campaigns and vote (electoral) campaigns, parent actions focus on making a system then take actions which, if successful, result in a change in student outcomes.

Further, while outcome measures tend to move in this linear fashion, they by no means always do. For example, an organization can begin by conducting training and then seek to measure satisfaction, knowledge and attitudes. Then, the organization can measure if parents in this training subsequently take action.

But if one of those intended actions is something like a house meeting or research meeting, the organization might again seek to measure changes in satisfaction, knowledge and attitudes from that house meeting, and potentially invest in seeing if parents participating in a house meeting then grow in their activism by taking other actions as participants or leaders.

Again, this does not mean everything should be measured. Not everything you care about needs to be or should be formally measured. Not everything can be measured. And everything you measure incurs a cost. Your organization should ‘Goldilocks’ what it measures. You should only capture measures that help your organization make better decisions to increase impact (and are practical to collect).

Last, all of these outcomes are interim outcomes on the path to positively changing student outcomes. Some parent empowerment efforts enable parents to take actions that directly benefit student outcomes. Others require influencing changes in the system which – if successfully implemented and adopted – then benefit student outcomes.

For more on linking parent empowerment work to student outcomes, click here.

A simple example from the supply side

Organizations can lay out a ‘wiring diagram’ of measures that are tracked over time, usually (but not always) in a clear linear progression with success going from left to right (in English) to achieve impact. This also becomes an integral component of an organization’s articulation of its intended impact and theory of change or theory of action.

Here is an example of what it looks like to lay out inputs, outputs and outcomes in a direct-service education program – in this case, ACT preparation:

Please note the “XX’s” in outputs and outcomes. Those are specific targets. Targets are not the same as outputs and outcomes. Rather, they are a specific performance an organization wants to achieve during a specific period of time. For more on Targets, click here).

A more complex example from parent empowerment work

Below is a hypothetical sequence of measures from a collective voice issue campaign.

Not surprisingly, the wiring diagram can get much more complex very quickly for parent empowerment work in linking from inputs to outputs to multiple steps of outcomes that ultimately arrive at student outcomes.

225 Franklin Street, Suite 350

Boston, MA 02110

617.912.8800

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 License (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Click Here to learn more.