FOUR EMPOWERMENT STRATEGIES

Overview

Strategy 1 – Parents as Partners: Parents exercising their power as co-educators of their children, either in collaboration with schools or through non-school resources.

Strategy 2 – Exercising their Choice: Parents exercising their power to (a) choose the school that they believe is the best fit for their children’s needs (within whatever constraints around choice exist in their community), and/or (b) make the myriad array of choices within a school that reflect the needs of their children.

Strategy 3 – Exercising their Collective Voice: Parents exercising their power through collective action on an issue campaign to influence those in authority to change policies.

Strategy 4 – Exercising their Vote: Parents exercising their power through electoral action to influence who holds a position of authority or to directly decide policy through a ballot initiative.

How these strategies work together (and why it’s important to consider them collectively)

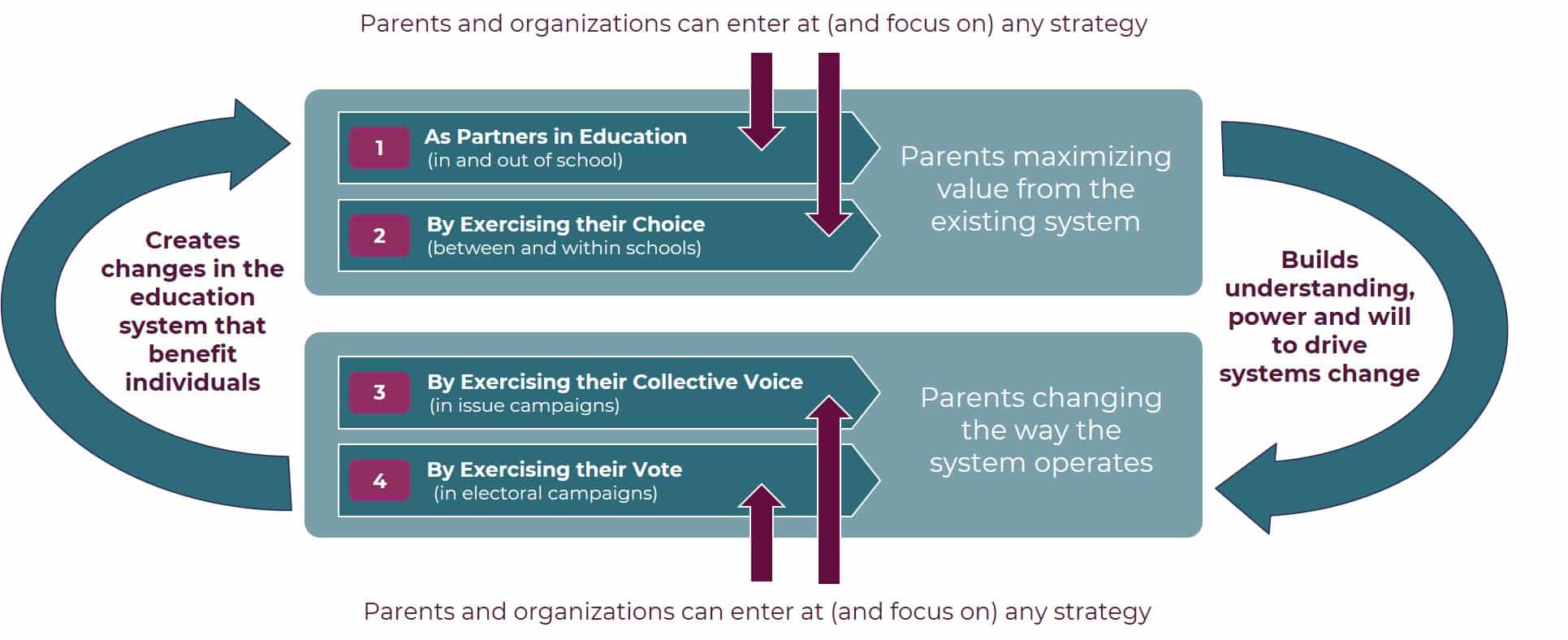

These strategies are not mutually exclusive and in fact work to reinforce each other:

Every education system operates under different political and policy conditions and has a different relationship with the community of students and parents it serves.

Some school systems have the “will” to be partners with parents and are looking for support to develop the “skill” to do it. At the other extreme are education systems where parents are fundamentally disenfranchised from their education system and the relationship is adversarial.

The first two strategies, parents exercising their power as partners in education and parents exercising the power of their choice, enable parents to focus on maximizing value from the existing system, which has intrinsic benefit for their children.

Additionally, for some parents, these first two strategies allow them to realize that there are educational opportunities they wish for their children that the existing system simply cannot provide without change. This realization builds understanding, power and will for a set of parents – some of whom will become leaders in their community – to exercise the power of their collective voice and/or exercise the power of their vote to fight for changes in the way their education system operates.

When these types of systems-change campaigns are successful, they also often require parents to again exercise their power as partners or exercise the power of their choice to ensure they and their children can fully access and adopt the benefits a changed system offers.

However, these strategies need not be employed linearly. Parents and organizations can begin with any of these strategies and pursue them in any sequence or combination over time.

Some organizations may exercise all of these strategies directly. Some organizations focus on a specific subset of strategies and collaborate with peers in their local education ecosystem to divide and execute – while mutually reinforcing the success of each other’s efforts.

Lastly, parent empowerment efforts are dynamic and cyclical. Organizations and communities can employ an ever-changing mix and sequence of these strategies to fit their specific local political, policy and educational performance context.

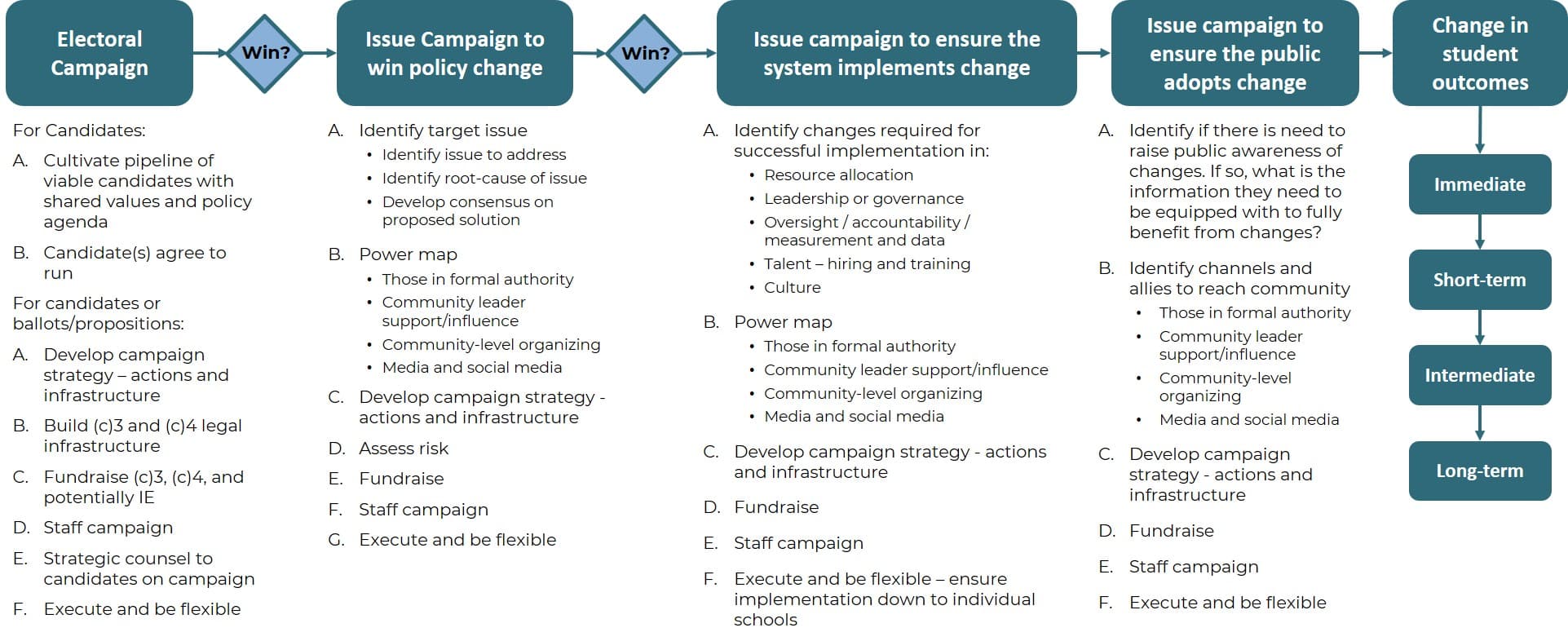

Campaigns: A plan to accomplish specific impact for a specific population in a specific period of time

We refer to work across all four of these strategies as campaigns, which we define as, “a plan to accomplish specific impact for a specific population in a specific period of time.” The term ‘campaign’ is more commonly used in issue and electoral work. But the above definition also holds true of work to enable parents to exercise their power as partners and to exercise their power of choice, and it is equally valuable to think of these strategies as campaigns to aid in planning, execution, learning, and attracting allies and resources.

Creating and SUSTAINING enduring change within and across these strategies is not a marathon or a sprint. Rather, it is a commitment to walk 10,000 steps every day.

To create impact, we have to accept that successful parent empowerment work is a long-game with no end.

Collective Voice and Vote strategies often require multiple campaigns (or campaigns-within-campaigns)

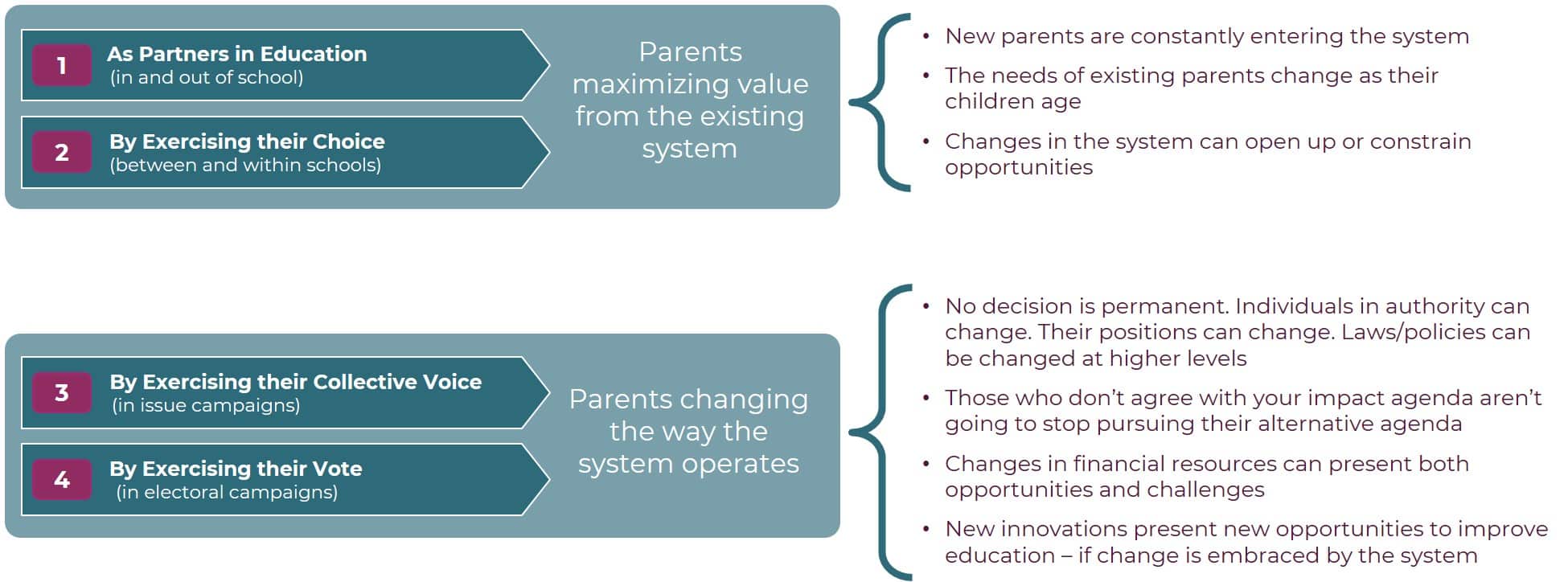

Campaigns to create change in any of these strategies are complicated. However, strategies with the goal of changing how the system operates are particularly complicated because they usually require not just a single campaign but multiple campaigns (or a large campaign with multiple campaigns-within-campaigns) – see graphic below.

Unfortunately, this is not commonly understood. Frequently the sector expects complete transformation in a single campaign, and/or assumes different types of systems-change campaigns create the same impact.

One parent empowerment CEO expressed concern that too often, “funders expect (c)4 electoral results from (c)3 issue campaigns.” This assumption – by anyone – is problematic at two levels.

First, electoral campaign success doesn’t achieve impact without translating into issue campaign success. Winning an electoral campaign to change who is in authority does not automatically lead to changes in the system. It leads to a change in who holds authority. Nothing changes until an elected individual exercises that authority.

Frequently, organizations must follow up a successful electoral campaign with an issue campaign that combines partnership and/or persuasion and/or pressure to ensure that those in authority have both the policy insight and also the political will to act to make policy change happen.

Unfortunately, too often systems-change efforts have failed to build and maintain the infrastructure of parent power following an electoral campaign that would enable an electoral success to drive an issue campaign success. As hard as winning an electoral campaign is, “You get someone elected, and then the real work begins.” This work is also not inherently adversarial, as it is sometimes stereotyped. People in a position of authority need the support of their constituency to make difficult decisions, which is why continued engagement by that constituency is so crucial. Sometimes it is about carrying pitchforks, but it is as often about carrying shovels to help build together.

Second, making systems change even more complicated, winning an issue campaign to change policy almost always requires a follow-up implementation campaign at varying levels of formality to ensure the system actually acts on a policy change (this is also true even of an electoral campaign to win a ballot initiative). It is inherently hard for systems to change. Unforeseen challenges to implementing policy change can arise. So can passive and active opposition from within the system. Change in circumstances (such as funding changes, change in who is in authority, etc.) can throw twists into getting change implemented. And those who are opposed to a given policy change will likely continue to pursue their agenda to prevent or reverse it.

Even when the system successfully implements a change, an organization may need to pursue yet another campaign to ensure public adoption. Does the public know that a change in the system is happening that could benefit their children? Do they know how to navigate and capitalize on this successfully? This is also often where a campaign or set of campaigns to change how the system operates benefits from complementary campaigns to help parents exercise their power as partners or exercise the power of their choice to ensure their children receive the full value from those system changes.

Only at the end of this multi-step journey can we then begin to measure the value created in terms of student outcomes.

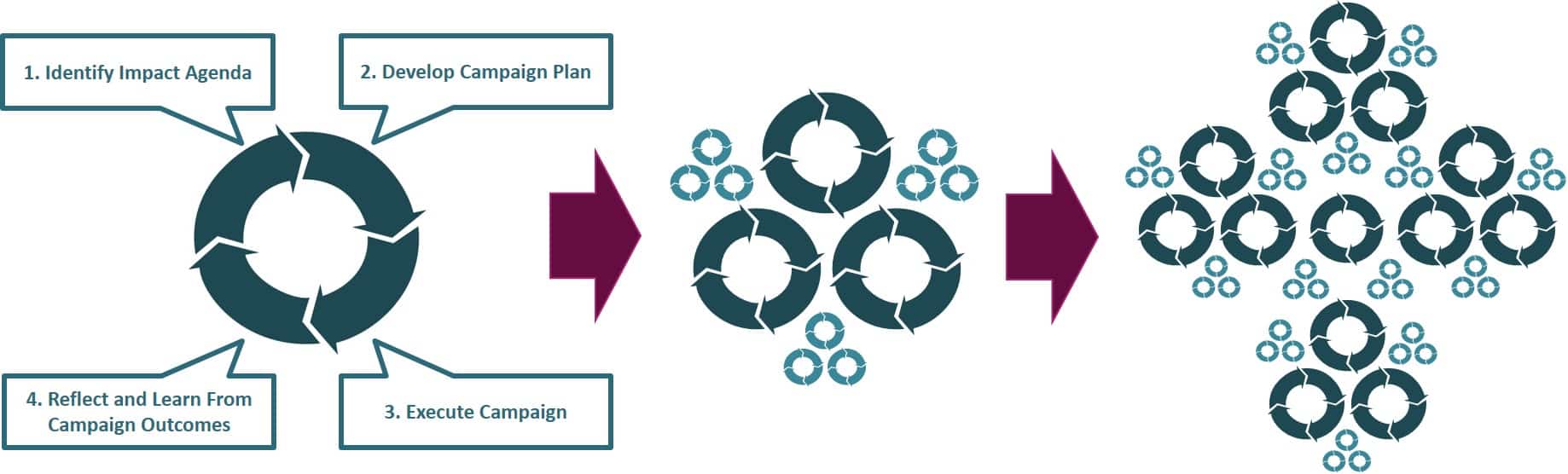

Last, campaigns – across all four strategies – don’t exist in isolation, but in an ecosystem of campaigns

There are many reasons why organizations need to think beyond a single campaign to multiple campaigns and even an ecosystem of campaigns (their campaigns and those of allies) to fully realize their impact agenda:

- Campaigns may not initially win and can require multiple campaign ‘cycles’ to achieve success.

- Campaigns may need to win at multiple levels (local, district, state) to fully realize an impact agenda.

- Change in conditions can require new campaigns to advance new opportunities and/or sustain/protect existing progress.

- Campaigns by those with a competing agenda can undo campaign progress you have made, requiring new campaigns.

- Success in one campaign can reveal the need for another campaign (in the same or different strategy).

- Success in one campaign can and should also build the infrastructure of parent power needed to take on other impact agendas.

- Campaigns may be focused not just on education but also on adjacent social issues that matter to communities.

225 Franklin Street, Suite 350

Boston, MA 02110

617.912.8800

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 License (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Click Here to learn more.