INFORMED PARENTS

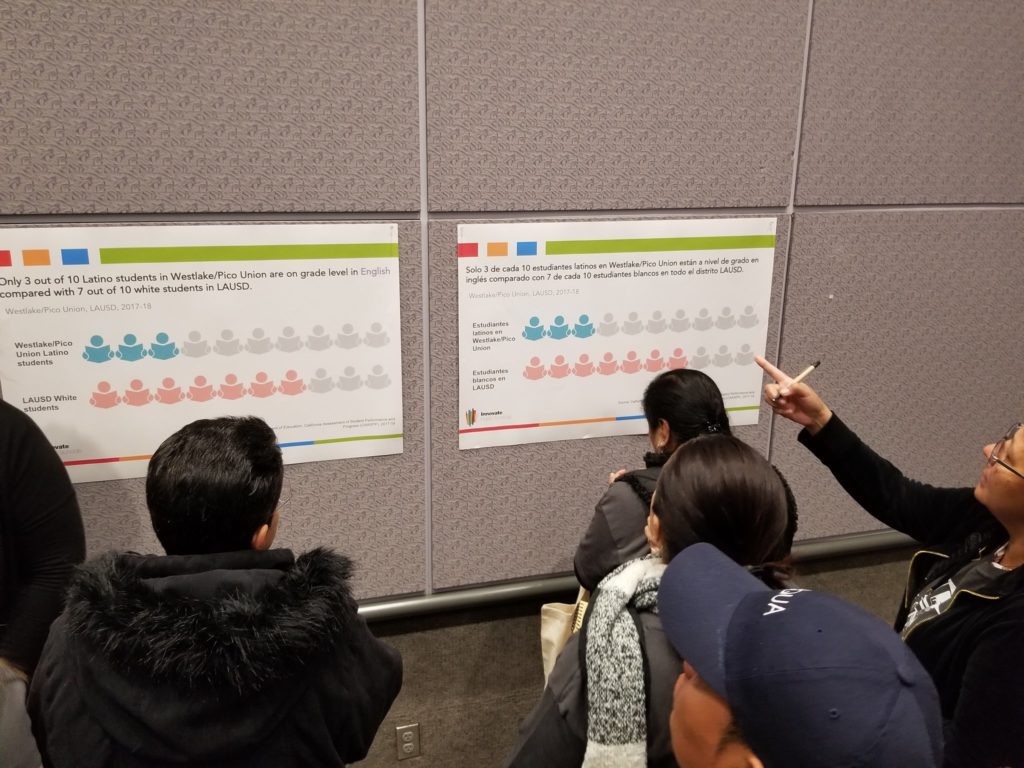

People don’t try to solve problems they don’t know they have. In too many school districts and cities, parents are not even aware of the inadequacy of their education systems. A recent report by Learning Heroes reveals that 90 percent of parents nationally believe their children are at grade level in reading when in reality only 34 percent of eighth-graders actually are. And this disparity holds true across all demographics.

People don’t try to solve problems they don’t know they have. In too many school districts and cities, parents are not even aware of the inadequacy of their education systems. A recent report by Learning Heroes reveals that 90 percent of parents nationally believe their children are at grade level in reading when in reality only 34 percent of eighth-graders actually are. And this disparity holds true across all demographics.

Many students and families in failing systems don’t find out that the system has failed them until it is too late. The life lesson of Maribel Gonzalez is a case in point.

“I grew up in South Central LA – in Watts, where there are a lot of good people but not a lot of opportunities,” she explains. “My teachers told my parents I was ‘well behaved and a pleasure to have in the classroom.’ I was the valedictorian of my graduating middle school and high school classes. I had the highest GPA of my graduating class.

“Yet when I arrived in college, I had to spend my first two quarters taking remedial courses before I could begin to accrue college credit. I did everything my high school told me I should do. My school told me I was ready. But it lied.”

Gonzalez ultimately overcame her lack of preparation and has become a leader in education activism (we’ll come back to her later).

Sadly, Gonzalez’s story is not an anomaly. If knowledge is power, too many parents are disempowered by not knowing the truth about their schools and the academic readiness of their children. Too often schools are telling parents that their children are doing fine, even when they are not. And formal school reporting — at the school, district, and state levels — is too often untimely edu-gibberish.

In order to truly know if students are getting an effective education, and to start on the journey to change things if they aren’t, parents need to be provided with clear, timely, actionable information about the performance of their children, schools, and school systems.

Unfortunately, even well-intentioned education reformers sometimes fall into the edu-gibberish swamp. We try to tell parents everything they can know (and also everything we know), without focusing on the bottom line of what they want and need to know. We get too academic about academics and end up not making a compelling, accessible, and relevant case to parents about the reality of the broken education systems they entrust their children to.

Last, the messenger is as important as the message. People are more willing to listen to hard truths from people they trust — members of the community or those who have earned credibility in the community.

225 Franklin Street, Suite 350

Boston, MA 02110

617.912.8800

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 License (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Click Here to learn more.